Remember the Tower Hamlets Neighbourhoods? As an experiment in political devolution they only lasted from 1986 to 1994, so you could be forgiven for having forgotten about them. Building a sense of neighbourhood identity was an essential element of the scheme and on a crisp and cold morning in January 2017, I went on a walk around Tower Hamlets to see what remained visually of the Neighbourhoods. Given that they had been abandoned 23 years earlier, I wasn’t hopeful of finding much…

I’ll come on to the walk and what I found in the next post, but first a recap on the Neighbourhoods. There is a whole history to be written about local politics in Tower Hamlets and it is well beyond my means to attempt such a thing, so please excuse the crude summary of this part of the story.

Tower Hamlets and its predecessor authorities (Poplar, Stepney and Bethnal Green), were traditionally solid working class Labour areas. In his excellent book Rebel Footprints (1), David Rosenberg brings to life the rich political history of the area and its central place in the growth of municipal socialism and the Labour movement.

In the early 1980s, when Labour’s new urban left assumed power in many Inner London Town Halls (and in County Hall), the Tower Hamlets Labour group remained on the right of the party. There had been no Lambeth-style revolution within the local Labour Group, so the job of filling the radical void was largely left to others. The “others”, in this case, were a highly organised “Liberal Focus” group.

Tower Hamlets in the 1970s and 80s faced many interlinked issues including severe deprivation, a deteriorating housing stock, the decline of the area’s traditional industries, the closure of the docks and rising racial tensions. Added to the mix in the eighties was a controversial interloper in the form of the London Docklands Development Corporation which took over strategic control of the regeneration of a large part of the Borough.

These factors (especially housing) appear to have created a fertile environment for the Liberals. The Liberal strength grew slowly with seven elected members from 1978-82 and 19 (out of a possible 50) from 1982-86.

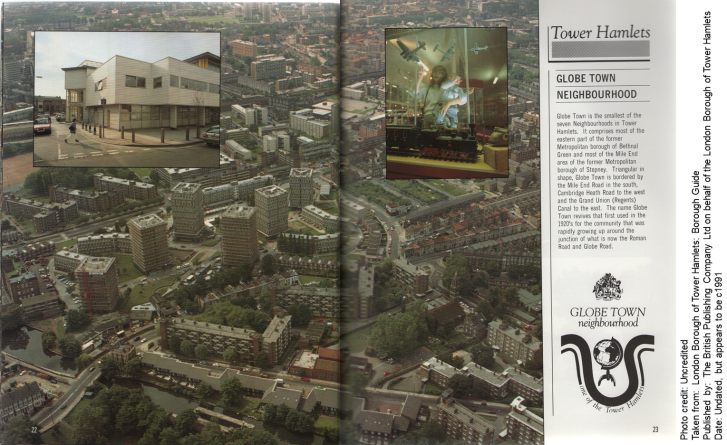

And then, in 1986, the Liberals took control of the Borough, with a one vote majority. Their manifesto “Power to the Hamlets” proposed a radical new form of decentralised local government. Seven Neighbourhoods were to be created: Bethnal Green, Bow, Globe Town, Isle of Dogs, Poplar, Stepney and Wapping. Each would be run by an autonomous local committee. Each would be given its own Chief Executive and almost all services, and a number of “back office” functions would be devolved down to Neighbourhood level. The change was immediate and by the end of July 1986 (following the May election) many of the structures required to give effect to the Neighbourhoods plan were in place.

The detail of how the Neighbourhoods operated and their effectiveness are covered superbly by Janice Morphet (2) and Vivien Lowndes and Gerry Stoker (3). What follows in the next section is based on their analysis.

The Neighbourhoods in action

The Liberal-controlled centre (through its Borough-wide Policy and Resources Committee) allocated annual budgets to the Neighbourhoods but thereafter it was up to the Neighbourhoods to control expenditure. One obvious point in respect of the devolved political structure is that it did not deliver complete local control to the Liberals. In fact, they only controlled four of the newly established neighbourhood committees in 1986, with Labour in the majority for the other three. Thus Labour found itself with more power than an opposition party might expect, but under a structure it didn’t agree with.

In the 1990 elections, the newly constituted Liberal Democrats consolidated their power, winning 29 of the Borough’s 50 seats. Unsurprisingly, they attributed their success to Neighbourhood scheme. As Lowndes and Stoker record, Labour admitted a degree of complacency on their part, perhaps assuming that they would automatically return to power in what was their natural heartland.

So, at the time of Lowndes and Stoker’s 1992 evaluation, the Liberal Democrats’ experiment in devolution was in full swing. How was it doing? The academics considered the perspectives of a number of stakeholders with particular focus on the operation of the Globe Town Neighbourhood (which, they noted, with a population of just 15,000 had become “one of the smallest but most powerful units of local government in the UK”). It really isn’t fair to summarise their comprehensive study in a few short paragraphs, so I apologise to the authors for attempting to do so.

They found that Globe Town’s impressively high levels of service-user satisfaction were not matched by those of other Neighbourhoods which remained below the norms for inner city authorities. Globe Town had used decentralisation as a platform for promoting customer-centric policies.

Their study suggested that citizen involvement in local democracy had been enhanced by the new structures, with an opening up of decision-making processes and high levels of participation observed. They concluded that an already strong sense of East End identity had been nurtured by the new structures. On the other hand, the primary citizen identity was that of “tenant” with other forms of community identity and organisation much weaker.

The evaluation found that Council staff experience was far more mixed. Although the Liberals had promised no compulsory redundancies in 1986, a large number of senior officers chose to leave of their own accord, to be replaced by a younger staff base attracted to the decentralisation model. The curate’s egg was further revealed in a staff survey conducted by the authors in which 50% described the management style of the Globe Town Neighbourhood as “boldly experimental but with a tendency not to consolidate gains”, with a further third describing it as “crisis management in an environment of chaos”. Yet only 12% felt that “bureaucratic management stifled good ideas”, which was surely low for a public sector institution.

As for Councillors, Lowndes and Stoker wryly noted that Globe Town’s Liberal councillors “found Neighbourhood political structures more to their liking than the sole Labour councillor”.

Crucially, the authors concluded that the simplicity of the decentralisation vision had a number of weaknesses. In focusing on the Neighbourhoods, the role of the centre had been undercooked and opportunities to share best practice between Neighbourhoods were lost as a result. And on a related point, they found that some decentralised functions could have been far more effective if they had been left alone and kept at the centre (e.g. libraries and archives).

The end of the Neighbourhoods

Whatever the academic conclusion on effectiveness (and it was far from clear cut), it was ultimately public opinion and the ballot box that killed off the Neighbourhoods. Despite the Liberal Democrats’ 1990 victory in the Council elections, public opinion was shifting. One much mentioned gripe centred on the difficulty in Council tenants moving home between Neighbourhoods – one former employee suggested to me that it was easier to move out of the Borough than within it. As the Independent (4) reported:

“An elderly resident living at one end of Salmon Lane in Poplar requiring the support of a relative that lives at the other end of Salmon Lane in Stepney would be unable to move under the old [Neighbourhood] system.”

The most controversial aspect of the whole story (one might be tempted to say “sorry saga” by 1993) related to the actions of local Liberal Democrat activists and allegations of racist leafleting. By making a series of claims that Labour-controlled Neighbourhoods disadvantaged the local white population in housing allocations, the Liberal Democrats ignited a race row that many linked to the 1993 by-election victory of the British National Party on the Isle of Dogs. Paddy Ashdown, then party leader, ordered an inquiry which went on to recommend the expulsion of certain party members and criticised various levels of the party structure for failing to address issues that it concluded had been known about for some time.

Embroiled in scandal, unloved by the national Liberal Democrat party and finally thrown out by the electorate (the Lib Dems won just 7 of the Council’s 50 seats in 1994), the Neighbourhood experiment was over. The incoming Labour administration quickly moved back to a more traditional local authority structure and the Neighbourhoods were no more.

In the next post, a journey round the Borough to explore the visual remains of this experiment…

This post was substantially revised in May 2021 to include more narrative on the academic studies of the Council’s effectiveness.

Notes

(1) David Rosenberg: Rebel Footprints: A Guide to Uncovering London’s Radical History, Pluto Press (2015)

(2) Janice Morphet: Local Authority Decentralisation – Tower Hamlets goes all the way, Policy and Politics Vol 15.2 (1987)

(3) Vivien Lowndes and Gerry Stoker: An Evaluation of Neighbourhood Decentralisation: Part 1 Customer and citizen perspectives, Policy and Politics Vol 20.1 (1992); and Part 2 Staff and councillor perspectives, ibid Vol 20.2

(4) Matthew Brace: Neighbourhoods abolished: In Tower Hamlets the new Labour council has destroyed a discredited scheme, The Independent newspaper (24 May 1994)

This is fascinating, I have been trying to find out information on this and Wapping in 1986, so came here after Tower Hamlets Archives. Thanks so much for this and the additional reading. Such an interesting period of time.

LikeLiked by 1 person